From a young age we are primed to choose a favorite color, but strangely as we grow up our preference often changes – and it’s largely due to influences outside our control.

n 1993, crayon-maker Crayola conducted an unscientific, but intriguing poll: it asked US children to name their favourite crayon colour. Most chose a fairly standard blue, but three other blue shades also made the top 10 list.

Seven years later, the firm repeated its experiment. Again, classic blue ranked in the top spot while six other shades of blue appeared in the top 10, including the delightful sounding “blizzard blue”. They were joined by a shade of purple, a green and a pink.

The dominance of blue in such lists doesn’t surprise Lauren Labrecque, an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island who studies the effect of colour in marketing. Like a Pantone-sponsored party trick, she’ll often ask students in her classes to name their favourite colour. After they respond, she clicks on her presentation. “I have a slide already made up saying ‘80% of you said blue’,” Labrecque tells them. She is usually right. “Because once we get to be adults, we all like blue. It seems to be cross cultural, and there’s no big difference – people just like blue.” (Interestingly, Japan is one of the few countries where people rank white in their top three colours).

Our selection of a favourite colour is something that tends to emerge in childhood: ask any child what theirs is and the majority – crayon in hand – will already be primed to answer. Infants have broad and fairly inconsistent preferences for colours, according to research. (They do show some preference for lighter shades, though.) But the more time children spend in the world, the more they start to develop stronger affinities to certain colours, based on those they have been exposed to and the associations they link them to. They are more likely to link bright colours like orange, yellow, purple or pink to positive rather than negative emotions.

One study of 330 children between 4-11 years old found they used their favourite colours when drawing a “nice” character and tended to use black when drawing a “nasty” character (although other studies have failed to find such links, so emotional associations and colour are far from straightforward). Social pressures – such as the tendency for girls’ clothes and toys to be pink – also have a strong effect on colour choice as children get older.

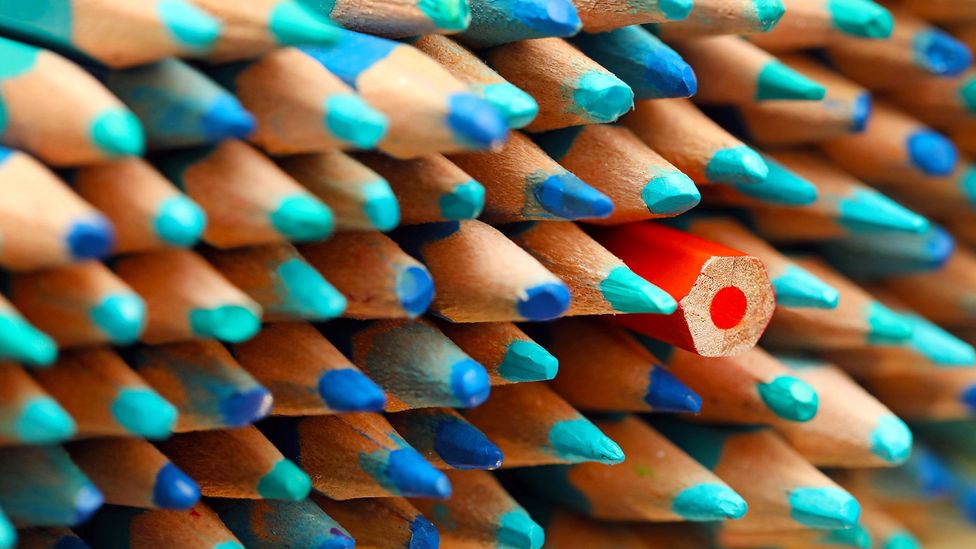

Despite the wide array of crayons on offer, children will often reach for a preferred colour time after time (Credit: Alamy)

It is commonly believed that as children enter their teenage years, their colour choices take on a darker, more sombre hue, but there isn’t much academic research to support this. Adolescent girls in the UK, for example, have been found to be attracted to purples and reds, while boys favour greens and yellow-greens. One study of British teenage boys’ choice of bedroom colour found they tended to choose white, while they listed red and blue as favourite colours.

These colour palettes seem to converge as people grow into adulthood. Intriguingly, while the majority of adults say they prefer blue colours, they’ll likely also dislike the same colour too: a dark yellowish brown is routinely identified as least popular.

But why do we have favourite colours? More importantly, what drives those preferences?

Put simply, we have favourite colours because we have favourite things.

At least that’s the gist of ecological valence theory, an idea put forward by Karen Schloss, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the US, and her colleagues. Her experiments showed that colours – yes, even beige – are far from neutral. Rather, humans layer meaning onto them, mostly drawn from our subjective histories, and so create high personal reasons to find one shade repellent or appealing in the process.

“This accounts for why different people have different preferences for the same colour, and why your preference for a given colour can change over time,” she says. As new associations accrete – whether through everyday exposure in the world around us or artificially by deliberate conditioning – this can cause what we love to change over time.

Think of colour preferences as a summary of your experiences with that colour: your regular daily experiences in the world influence that judgement – Karen Schloss

Schloss finessed this theory via several experiments, including one at the University of California-Berkeley. She and her collaborators showed volunteers squares of colour on a screen while prompts asked them to rate how much they liked them. Then the researchers stepped away, as if to suggest a new experiment was starting.

They returned to show those same volunteers coloured images again, except this time, instead of plain squares, they saw objects. Each image was dominated by one of four shades. Yellow and blue-heavy images were used as the control: these depicted neutral objects, like staplers or a screwdriver. Red and green photographs, however, were deliberately skewed. Half the participants saw red images that should have evoked positive memories, such as juicy strawberries or roses on Valentine’s Day, while the green images they were shown were designed to disgust, such as slime or pond scum. The other half saw a set that reversed these associations: think red raw wounds versus green rolling hills or kiwi fruit.

Running the colour preference test again, Schloss and her team saw a change in preference. Volunteers’ choices had shifted towards whatever colour had been positively emphasised while there was little decrease for the negative shade. The next day, she brought them back and ran the tests again, to see whether that preference endured overnight – it didn’t. The shift induced by the experiment appear to have been over-ridden by the colours participants experienced out in the real world, according to Schloss.

“It tells us that our experiences with the world are constantly influencing the way we view and interpret it,” Schloss says. “Think of colour preferences as a summary of your experiences with that colour: your regular daily experiences in the world influence that judgement.”

Schloss’s work on colour preferences may also inadvertently go some way to explain blue’s position as such a widespread favourite. Blue’s reign has continued uninterrupted since the earliest recorded colour studies, which took place in the 1800s. And most of our experience with the colour are likely to be positive, like idyllic oceans or clear skies (“having the blues” is an idiom restricted to English). In the same vein, her work also offers a clue for why that muddy brown colour is so reviled, associated as it is with biological waste or rotting foods. For a brief period each year, though, this shade finds favour, largely thanks to changes that occur in the natural world.

Perhaps surprisingly, our preference for colour changes as we get older, largely due to our experiences in the world around us (Credit: Melpomenem/Getty Images)

In an experiment intended, at least in part, to unpack whether favourite colours were a static component of someone’s identity, Schloss and her team asked volunteers in New England to track their colour likes and dislikes weekly during the course of the four seasons of year. Their opinions seemed directly influenced by nature, with likes or dislikes rising and falling in sync with nature’s palette. “As the colours of the environment were changing, their preferences were increasing,” she says. The greatest uptick came in autumn, when warm colours – think dark red and orange – earned heightened plaudits, before tumbling at the same time as the leaves.

Asked to speculate as to why autumn saw such a surge, she suggests two explanations. First, the area where she conducted that research is famed for its autumnal displays – leaf-peeping is a tourism staple in New England – so volunteers might have been primed for that preference. More intriguingly, though, she also believes that there’s an evolutionary aspect in play – the sharpness of contrast. “It’s fascinating to speculate perhaps it’s because it’s kind of quick, this rapid, dramatic change to the environment – so fast, and then it’s gone. Winter is a lot of white and brown, but we’re not outside as much to see it.”

The environment we live in nudges our colour preference in other ways too. Another study Schloss conducted looked at students at University of California-Berkeley and Stanford, showing that the varsity colours of a college influenced the hues they picked as favourites. The more a student said they endorsed and embraced the values and spirit of the school, the higher that preference rose.

It’s a big misconception that babies can’t see colour from birth – Alice Skelton

It’s easy to assume that the ecological valence theory would need time to take hold, for us to embed those social cues in the world we see. But experimental psychologist Domicele Jonauskaite says that’s wrong. She studies the cognitive and affective connotations of colour at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and has looked at how boys and girls view blue and pink – they articulate, and demonstrate, learned colour preference at a young age.

Girls’ love of pink forms on a bell curve, peaking at early school age – around five or six – before dropping off by the time they’re teenagers. “But the boys avoid pink from an early age, at least five or so. They think ‘I can like any colour – just not pink’. It’s really rebellious for a boy to like pink,” she says. “And among adult men, it’s hard to find someone who’ll say, ‘pink is my favourite’.”

Some researchers in the past have proposed that this particular colour preference, anchored in gender, is evolutionary: women were the gatherers in hunter-gathering societies, that theory goes, and would therefore need a preference for colours associated with berries. That’s utter rubbish, says Jonauskaite, who cites several recent papers looking at colour preference in non-globalised cultures – villages in the Peruvian Amazon, for example, and a foraging group in the northern reaches of the Republic of Congo. None of their female children displayed a preference for pink. “In order to have this preference, or dislike, for boys, that aversion needs to have a coding of social identity,” she says. In fact, pink was seen as a stereotypically male colour prior to the 1920s and only became associated with girls midway through the 20th Century. (Read more about the pink-blue gender preference myth.)

Even the youngest children can perceive, and rank, colour, suggests Alice Skelton, who helps run the Sussex Colour Group & Baby Lab, at the University of Sussex in the UK. Her particular area of interest is in babies and children, aiming better to understand how early preferences in colour translate into aesthetic preferences later in life. “It’s a big misconception that babies can’t see colour from birth – they can,” she says, noting that the eye’s development is uneven. The receptors which perceive greens and reds are more mature at birth than those which process blues and yellows, so intense reds, in particular register most easily in newborns.

If your choice of colour makes you stand out from the crowd, it could say something about how sensation seeking you are (Credit: Alamy)

The ecological valence idea – that we yoke meanings onto colours from the objects we encounter in the world – holds true even among the youngest. “Children will only pay attention to colour when it has a function associated with it. They won’t really pay attention to colour unless they learn something from that,” Skelton says.

Imagine there are two bottles. One is green, the other is pink. The green-coloured bottle contains tasty liquid, the pink one is a sour mix. Children will note, and remember, those colours, because recognising their difference provides a cognitive bonus. “It’s like a ripe banana – colour is a useful cue to some property of an object,” says Skelton.

That ripe banana, of course, could be a yellowish-brown, the same shade that squeamish adults tend to shun in laboratory tests. Skelton offers solace to anyone whose colour preference doesn’t fit the domineering rule of blue. Those drawn to unpopular shades could be products of a particular period, cherishing positive memories from their childhood – think 1970s babies snuggling on bouclé brown sofas. But there’s another intriguing possibility. Most humans are drawn to visual harmony, pleasure, and to easy sensations evoked by often-positive blue.

“It might be that while some are trying to achieve homeostasis, other people are sensation seekers, much like people are larks and night owls,” she says. “Think about artists, whose main job is to look for stuff that challenges their visual system or aesthetic preference.”

They’re the ones, doubtless, who didn’t reach for the blue crayon.