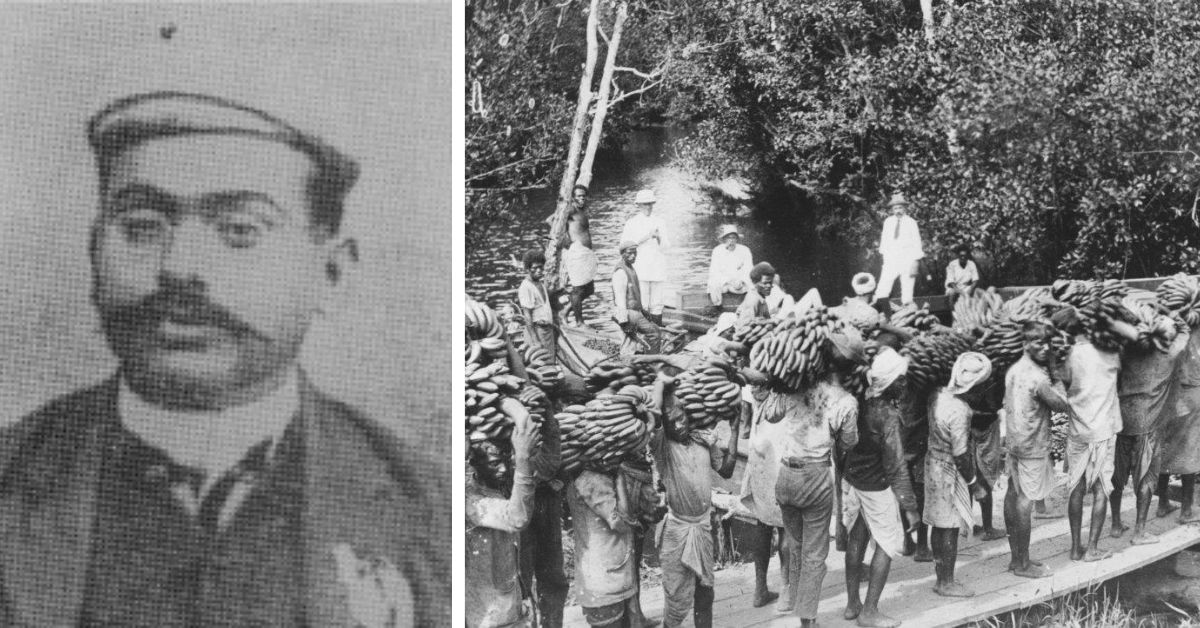

India’s maharajahs or rulers of princely states are commonly viewed through stereotypes of elephants, dancing girls, and grand palaces. Historian Manu Pillai revisits their legacy.

If you look beyond the bejewelled figures, palaces and opulent courts, you’ll notice something telling about India’s maharajahs: that they have largely been scorned and mocked, or treated with voyeuristic curiosity.

The British, in their day, cast “native” princes as decadent figures, more interested in frivolous sex and fancy dress than in government.

One white officer, for example, loudly proclaimed the typical maharajah as “monstrous and bloated in bulk, hideous and disgusting in appearance” and “decked with earrings and necklaces” like a dancing girl. Unlike white men, these were not manly figures of authority, but effeminate “scoundrels”.

The stereotype held for decades. In 1947, Life magazine joined the chorus through a statistical exercise which declared that the average maharajah had “11 titles, three uniforms, 5.8 wives, 12.6 children, five palaces, 9.2 elephants, and not less than 3.4 Rolls Royce cars”.

It was all droll and entertaining, even if the numbers are misleading. After all, of the supposed total of 562 “states”, most were microscopic estates with little political relevance.

To lump 100-odd bona fide princes, ruling over millions, with glorified landlords and aristocrats owning a few square kilometres of real estate, not only watered down their status, it also reduced them to a caricature: something akin to equating Queen Elizabeth with a country squire.

The fact, however, is that princely territories – spread over two-fifths of the Indian subcontinent and not under direct colonial control but linked through treaties and agreements with the Raj as vassals – featured rulers who were anything but the stereotype of glitter and parade.

As Life acknowledged in the same piece, Cochin’s maharajah was more likely to be found bent over a Sanskrit manuscript than in the lap of a concubine, while Gondal’s recently deceased ruler was a trained doctor.

The big states were not ruled by “tin-pot” dictators drowning in wine and orgies, but by serious political figures, who saw their kingdoms as legitimate political spaces.

Of course, the charge of princely eccentricity has some truth – one maharajah saw a Scottish regiment and immediately dressed his brown soldiers in kilts and pink tights, while another is said to have believed he was Louis XIV reborn among Punjabis.

But India’s princes hardly held a monopoly over such idiosyncrasies. British monarchs had just as colourful pasts, as did elected politicians; in fact, even a man like Lord Curzon – among the stuffiest viceroys sent to India – had it in him to once play tennis stark naked.

The image of the maharajahs as “self-centred fools”, then, not only misses the more interesting story but actively conceals it, as I discovered while researching my new book.

Mysore’s prince in southern India had elephants but also presided over a regime obsessed with industrialisation.

In Baroda, in the west, a journalist found that the maharajah there allocated $5 to every 55 of his subjects for education, as opposed to $5 per 1000 people in British India.

Meanwhile Travancore, in present-day Kerala, was celebrated as a “model state” for investments in schools, infrastructure, and much else.

Indeed, it was in the princely territories that many early discussions on constitutionalism took off in India.

So why is it that we only talk of harems, flashy cars, and sex scandals, when we think about the princes?

For one, it was a convenient line for the Raj, presenting colonial officials as well-meaning, upright nannies, struggling to discipline a band of spoilt (brown) schoolchildren. To acknowledge that brown men could not only govern, but also in many cases, beat the British would expose the empire’s so-called mission to “civilise”.

The story also plays down the paranoia and fragility which defined the Raj: though the princes were formally “pillars of the empire”, in practice they were restive partners, forever testing their overlords.

Baroda, for instance, was the source of revolutionary anti-British literature, printed under such innocent titles as “Vegetable Medicines”. Mysore would not tolerate the local press going after its royal family, but coolly allowed editors to criticise the Raj.

Jaipur’s rulers cheerfully fudged their accounts, concealing millions in revenue to avoid paying a higher tribute. Besides, multiple rulers provided financial support to the nationalist Congress Party in its fight for independence. Curzon, in fact, was convinced even in the 1920s that there were many “Phillipe Égalités” (after a Bourbon prince who supported the French Revolution) among the princes, with an “ardent sympathy” for the nationalist cause.

Odd though it may sound now, for much of the freedom struggle, the princes were actually seen as heroes.

The achievements of the bigger states brought pride to nationalists – including Mahatma Gandhi – dismantling as they did the racist trope that “natives” could not rule themselves.

But by the 1930s and 1940s things changed. In many principalities, often due to their own success in widening access to education, demands emerged for democratic representation. On the eve of the British withdrawal from India, many maharajahs became violently repressive, tarnishing their wider legacy.

The poor reputation the princes are saddled with today – where it does not stem solely from colonial stereotypes – comes from this endnote to their story.

But if history gives any lessons, it is that everything is more complex than it appears.

And this is true of the maharajahs also, among whom were deft modernisers and shrewd politicians – a detail for too long hidden behind stale talk of dancing girls and elephants.

Manu Pillai is a historian and the author of False Allies: India’s Maharajahs in the Age of Ravi Varma

You might also be interested in:https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.44.0/iframe.htmlMedia caption, India’s gay prince opens his palace for LGBT community