In spite of spending just four years in Mauritius, Manilal Doctor was able to implement reforms that resulted in Indian labourers transitioning from a state of indentured servitude to being recognised as individuals entitled to basic rights and freedom.

Slavery was abolished in the 1830s but the gruelling fate of the Indians in Fiji — a country in the South Pacific that also has status as an archipelago of more than 300 islands — was persistent, albeit in other forms that did not come under the banner of ‘slavery’. Instead, an indenture system was in place here, introduced by the French in 1826 and adopted by the British four years later.

While the Indians were looking at unending years of misery and despair, one man landed on the shores of the island in 1907. Whilst his stay was short, a total of four years, the changes brought in by him were revolutionary in every sense.

Manilal Doctor, an envoy of Mahatma Gandhi has gone down in history for being a beacon of hope for the Indians. From being indentured labourers, he helped them to become people entitled to their rights and freedom.

Here’s how Manilal’s four years spent on the island changed the course of history.

Born to lead

It all started with a letter.

Addressed to Mahatma Gandhi, the letter implored the social reformist to heed the pleas of the people of Fiji. These were Indians, who in their quest of finding work and a better life in the archipelago, had signed up for a cruel fate. The Indians highlighted their concerns about the mistreatment they faced at the hands of the Britishers, right from their legal rights being ignored to being forced to do arduous work in the cane fields.

Gandhi, who was in South Africa at the time, was saddened to hear about the plight of these Indians and had the letter published in Indian Opinion, a newspaper that he’d established. The daily had a massive reader base, including Manilal Doctor. Upon reading the letter, he was inspired to offer his services and made a trip to South Africa to meet Gandhi.

The latter convinced him to move to Mauritius and lighten the plight of these Indians by using his legal knowledge to get them their due rights. An anecdote tells of how the people of the island were so enthusiastic about finally getting a leader that they pooled 172 pounds together. The money would suffice to pay for Manilal’s ship fare, a home and law books.

Le Mauricien, a French language newspaper, chronicles the many efforts of Manilal Doctor during his stay in the island nation.

“His stay in our midst is full of historic events that have become the rich ingredients for historians to delve into at all ages. He is remembered among Indo-Mauritian historians to have founded the ‘Young Men’s Hindu Association’, the ‘Local Arya Samaj Movement’, and the ‘Hindustani’, a bilingual daily, all these to defend and safeguard the interests of the working-class Indians in this country,” reads an excerpt from an article.

A lifetime’s work in four years

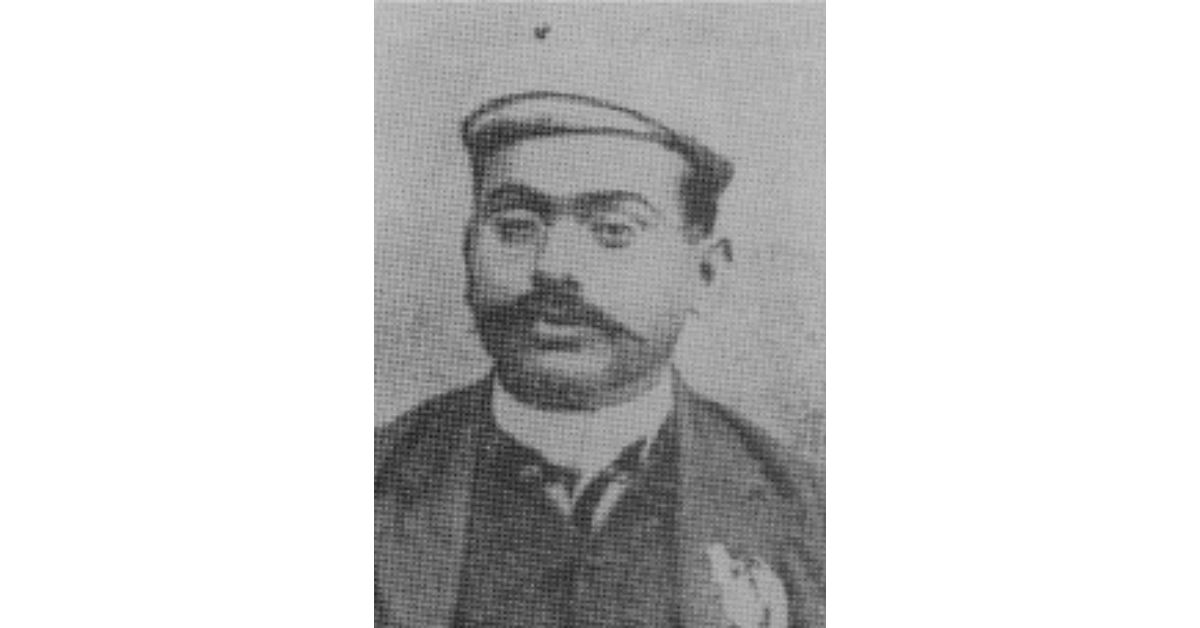

The first issue that Manilal focused on tackling was the “Double Cut” and the “Corvée” systems prevalent on the island. This meant unpaid and forced labour by the Indians for hours on the cane and sugar plantations. And as Totaram Sanadhya, an indentured labourer who later became a Hindu priest, wrote in his book My Twenty One Years in the Fiji Islands, “a smart way of getting the work done”.

“Fiji’s true inhabitants cannot do the work of a labourer well. Their own nature is wholly unsuited to this activity. In the cane fields, one has to do the same work every day (they get fed up from doing this). But the Indian coolies are utterly well-suited for this very activity, and planters generally give the work to them,” reads an excerpt.

Through the brutal systems implemented in the fields, the inhabitants and landlords would declare the Indians as vagrants, and with the help of a justice system and the district magistrate, send them to prison. Finally, the hours of work done by the helpless Indians would yield harvests for the planters and help them financially while the Indians rotted in jail.

Manilal Doctor integrated his legal knowledge into the judicial system ensuring that the labourers were rightly treated. Manilal, along with giving the Indians legal advice, would also write their letters and petitions and fight their cases in court for a low fee. As the indentured labour system began fading out in 1916, he then focused his efforts on helping the Indians get political rights.

An organisation is born

The Indian Imperial Association of Fiji was inaugurated on 2 June, 1918, and meetings were frequently held and presided over by the chairman, none other than Manilal Doctor.

Following the meetings, the streets would be filled with chants of “Hindu-Mussalman ki jai,” “Mahatma Gandhi ki jai” and “Mahatma Tilak ki jai”, which irked the British. The meetings along with demands voiced by the Indians finally culminated at the end of the indenture system of labour on 1 January, 1920.

However, empowered by their leader Manilal, the Indians continued their strikes not willing to settle for long working hours. This, the British decided was enough retaliation they had seen.

In his book, The Fiji Indians: Challenges to European Dominance, 1920-1946, Kenneth Gillion, a New Zealand academic wrote, “On 27 March an Order was made under the Peace and Good Order Ordinance, 1875 prohibiting Manilal, Mrs Manilal, Harpal Maharaj (a Hindu priest) and Fazil Khan (a wrestler) from residing for two years on Viti Levu or Ovalau or within Macuata province on Vanua Levu. Legally, this was not a sentence of deportation, but it amounted to the same thing, as the areas named were the main areas of Indian settlement and the only places where Indians could earn a living in Fiji.”

It was time for Manilal to leave the island he had helped. Through the course of the four years that he spent there, over 60,965 Indian labourers were helped.

While the lawyer returned to India, where he passed away in 1953, the impact of his work lives on in history.

You may also like

Liver Problems and its Ayurvedic Treatment