India’s U-turn on wheat exports is a result of incorrect estimates derived from an archaic crop forecasting system devised 4 centuries ago by emperor Akbar’s finance minister.

New Delhi: Tharavamat Nanda Kumar vividly remembers the day, some 16 years ago, when he visited the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO).

A few days before the visit, Kumar, then the additional chief secretary of Jharkhand, had received an SOS call to report to Delhi and take over as secretary of food and public distribution. The country was going through a wheat crisis. Signs of a shortage were evident. Public stocks were dwindling.

The government, headed by Manmohan Singh at the time, had already decided to import wheat.

When Kumar, then 56, went for a briefing at the PMO, he was advised by an official: “Do not rely solely on the wheat production estimates from the agriculture ministry. Talk to traders, look for price signals from domestic and international markets, do your own homework and research before making a decision.”

Kumar followed the advice diligently. But the ministry he once served seems to have failed to learn from its series of missteps between 2003 and 2006 — when India exported wheat to draw down public stocks and later resorted to imports.

In 2022, wheat is back in the news after a record-breaking heat wave in March blighted the crop. The event followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in end-February which pushed global prices of wheat to record highs. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, global wheat prices were 56 per cent higher year-on-year in May.

Mid-February, the agriculture ministry estimated the crop production to be a record 111.3 million tonnes (second advance estimate).

“That was the number the food and commerce ministries took to make critical policy decisions including pushing export. And, as we know by now, those numbers were not accurate,” Kumar told ThePrint over the phone from Kerala where he now lives.

Mid-April, India’s food and commerce minister Piyush Goyal said India is targeting to export 10-15 million tonnes of wheat and fill a part of the supply void created by the Russia-Ukraine war. In less than a month, India had to take a U-turn after realising the crop size is smaller than estimated.

According to Kumar, there is “an urgent need to clean our data systems in agriculture”.

Speaking to ThePrint, a senior official with an international commodity trading firm, who wished to not be named, said that the system to determine yield estimates still relies on an archaic system developed by Raja Todar Mal, the finance minister of Mughal emperor Akbar, more than 450 years ago, adopted and refined during British rule.

And it’s not just wheat, yield estimates of cotton and horticulture crops like tomato, too, can be erroneous.

‘Bad data used at the wrong time’

After the food ministry failed to purchase enough wheat for its food security schemes — public procurement fell short of target by a staggering 25 million tonnes — the government banned exports on the evening of 13 May.

The purpose was to tame domestic food inflation, which surged to a high of 8.4 per cent year-on-year in April.

On 19 May, the agriculture ministry revised wheat production estimates down to 106.4 million tonnes (third advance estimate).

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agricultural Service released an even lower number in late May — 99 million tonnes — following field visits to major wheat-growing states. Current trade estimates hover between 90 million tonnes and 100 million tonnes. No one seems to know the exact production number.

“India is building a digital Agristack and has technologies like drones, remote sensing, artificial intelligence and machine learning at its disposal, yet it is relying on the dubious integrity of the local patwari (revenue officer) who often records data without visiting the field. Only a fraction of crop-cutting experiments for yield estimation actually happen on ground,” Kumar said. “It’s a case of bad data used at the wrong time.”

Crop-cutting experiments (CCEs) are conducted in randomly selected plots of specific size to record the quantity of grains harvested to estimate yields.

According to the agriculture ministry’s Directorate of Economics and Statistics, about 1.4 million CCEs were carried out by state governments in 2016-17, to estimate yields of grains and pulses. The technical guidance and sample checks during the process is provided by the National Statistical Office.

In addition, the central ministry is currently running two projects, FASAL (Forecasting Agricultural output using Space, Agro-meteorology and Land-based observations) and CHAMAN (Coordinated Horticulture Assessment and Management using geo-informatics), for more accurate estimates. But results are yet to show.

This year, wheat may be in the limelight but cotton, too, shares a similar fate. The agriculture ministry overestimated the area planted, but a sharp drop in supplies led to a surge in prices compared to last year, said the senior official with an international commodity trading firm quoted earlier.

“When it comes to yield estimates, the budgets are so low that local revenue officials seldom visit the field for CCEs. There is hardly any use of ground truthing aided with satellites or remote sensing. Decisionmakers still rely on a system developed by Raja Todar Mal,” the official added.

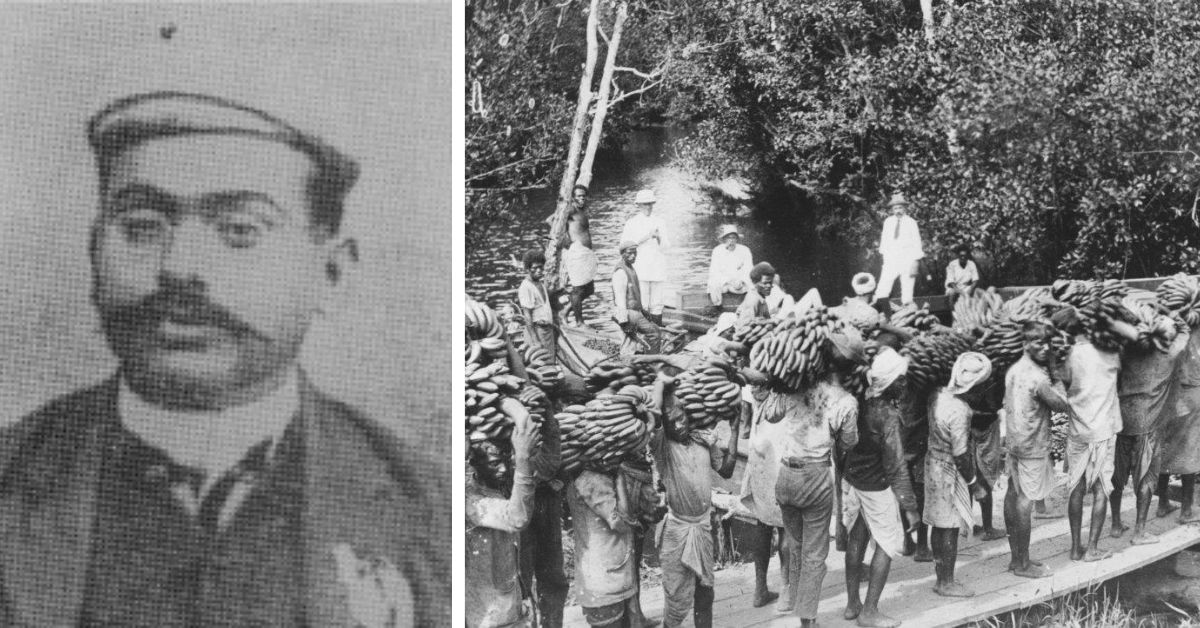

Todar Mal, finance minister of Mughal emperor Akbar who ruled India between 1556 and 1605, is credited with putting in place the architecture of a revenue collection system after a thorough survey of crop production and prices.

Now, the over-reliance on an archaic system also means that farmers do not have reliable commodity intelligence while taking planting decisions.

“In the absence of a robust futures market, farmers often take past prices as the only guidance while choosing between competing crops, leading to higher volatility,” said Arshad Perwez, Chief Revenue Officer at Our Food, a Hyderabad-based farm supply chain startup.

A little too late

According to the agriculture ministry, advance estimates of production of major crops largely rely on area statistics before actual crop-cutting experiments are carried out.

For instance, the final production estimates for wheat harvested in April-May this year will be released in February 2023, a little too late for food management and trade policy decisions.

“The advance estimates of crop production can at best provide a signal… we function with the belief that random errors will cancel each other out at an aggregate level,” said Avinash Kishore, research fellow at the New Delhi office of the International Food Policy Research Institute.

“Our entire data system is designed for grains, although in value terms horticulture, milk and livestock has far surpassed foodgrains. Yet, data gathering on these is horribly poor.”

Kishore cited several examples of non-existent or poor-quality data. For instance, milk production is known to fall sharply during the summer months and surge during the winter. But there are no estimates of the impact of heat on milk production. So, it remains unclear how the ongoing heat wave is impacting cattle productivity.

Similarly, production estimates of horticulture crops that are harvested in short intervals (multiple pickings), such as mangoes and tomatoes, are ridden with errors — a reason why volatility in prices of perishables is a recurrent pain for both consumers and farmers.

Over the past year, average tomato retail prices rose by a staggering 146 per cent (as on 5 June), shows data from the consumer affairs ministry. This might prompt farmers to plant more, leading to a crash in prices and tomatoes dumped by the roadside a few months later.

“We have no reliable data on value chains or how much food is wasted during transit, at warehouses or on the neighbourhood vendor’s push-cart. When a banana is over-ripe, it is sold for a lower price. The loss of value there is larger than the quantity loss,” Kishore said. “To become the export powerhouse India desires to be, it needs to pay attention to these data gaps.”