I was still lying on my back, the white nylon bib around my neck, the sour taste lingering in my mouth, when the hygienist said, “Oh honey, you’re beautiful. You should take care of your smile.” The dentist had just given me a twenty-five-thousand-dollar estimate to get all of the problems with my teeth fixed. “It’s like buying a car,” he said. And I wondered what kind of car he thought I owned.

The most expensive vehicle I had ever bought was the nine-year-old Toyota Corolla that I scored for five thousand dollars. I was proud of myself, too, for finding that bargain with three months of saved up overtime cash and weeks of ad-scouring for a low-mileage number with front-wheel drive and working air-conditioning. But teeth are not like cars. There are no bargains to be found if you want a pretty smile.

The dentist told me about Care Credit—a card specifically made for dental- and health-related needs. Conveniently, I could apply right there in the office. “Okay,” I said, knowing that even at forty years old my credit had never scored above six hundred. But I complied and filled out the paperwork anyway. What did it matter? I had already been humiliated walking into that office with a mouth full of cavities and missing teeth. It surprised me when the dentist came back and told me I was approved for four thousand dollars.

Working full-time as a community college professor for six years had made a difference, I guessed. That, combined with the full allowable withdrawal of three thousand in flex spending, he told me, would get me one implant for one tooth. And then we could move on from there. At that rate, it would take me years to fix all the damage.

Teeth are not like cars. There are no bargains to be found if you want a pretty smile.

I tried not to think about how long it would take. I tried to shut out the condemnation that echoed in my head. The dentist put a temporary fix on my molar, then we made a plan for the implant over the next six months and also to get my teeth whitened. I think he added the whitening as a bonus to keep me coming back. He had already pegged me as a flight risk. I drove home that day a sobbing mess—the Novocain’s punch still swollen on my face, the gauzy white pad reddening my uncontrollable spit, and a deep shame I couldn’t explain.

Our teeth tell stories about us, about the way that we have lived, about where we come from, about our habits, our health, and status. Teeth are stronger than bones. Even thousands of years after the body is gone, the narrative cemented into the layers of enamel can chronicle a life, like the rings inside trees. Cavities catalogue a long history of carbohydrates and sugar consumption; the wearing of enamel reveals poor diet and nutrition; micro-wear on teeth shows the way a person chews. Archaeologists can tell, for example, that Neanderthals lived through high-stress events that disrupted the enamel formation during childhood. Events like illness or malnutrition that have lasted up to three months can appear on teeth.

When I was in my twenties and had my first tooth pulled, the dentist, upon looking inside my mouth, said I must have had a high fever when I was in grade school. I was surprised at how he knew this, at how accurately my enamel told the tale. But what it didn’t tell him was that my mom had left my dad again. Their relationship had blossomed at AA meetings, and after they got married it was marked by days-long fights and periodic trips to rehab and the psych ward. But even though they split up often, they always ended up back together.

Mom couldn’t make enough money by herself to take care of both my sister and me. This time, Mom had taken us to a shelter where there were dozens of other mothers and their children sharing rooms and common areas. Gina and I were maybe six and seven. My first permanent molars might have been just erupting at that point. I had been sick for over a week, and when my fever rose to 105 and I was shaking in my bed, delirious, the women pooled their money so that Mom could taxi us to Emergency. The doctor diagnosed me with strep throat, said it was good we caught it in time; otherwise, I was at risk of getting rheumatic fever. I spent most of that night lying behind a curtain on a gurney in Emergency, Mom and Gina by my side. Together we waited until the antibiotics and Tylenol brought my fever down.

When I was ready to be discharged late into the morning, it was Dad who picked us up. Mom had called him from the hospital. We had been gone for only a few weeks that time, but it felt like no time had passed, because everything seemed right again when we got into the house and there was ice cream waiting for us.

*

Like millions of Americans in poverty, my parents never had dental insurance. Even when both of them were working, they had jobs that did not offer that kind of remuneration. Dental care and prevention were always lowest on the list of our problems. I was in sixth grade when my family moved to Berlin Street. It was a roach-infested upper-level of a duplex on Rochester’s northeast side. Mom had just gotten back from another sixty days in the psych ward and Dad had lost his job again.

Those eight hundred square feet were the cheapest Dad could find on our welfare allotment. Once a month, the landlord, who thankfully lived below us, scheduled the exterminator, which always turned into two days of hell for me and Gina. Our little family of four spent the evenings prior removing all of our dishes, silverware, and food from the cupboards to place into boxes on the table.

We pulled the furniture away from the walls so the spray could get into every crevice. The fumigation was usually scheduled for a weekday to be sure everyone would be out of the house for six or seven hours. When we got home, we’d have to deal with the death—thousands of roach carcasses on their backs, some still squirming, unable to turn over. Armed with brooms, dustpans, and large garbage bags, we moved from room to room opening the windows to dissipate the chemicals and sweep those hard-shelled, six-legged monsters that multiplied by the thousands.

Roaches weren’t the only pests our family lived with. In our many apartments, we often had mice and rats. We learned to keep our cereal, pasta, and cookies in recycled plastic and glass containers so that the little chewers wouldn’t munch through the bottom corners and force us to waste precious food. There were always ants, spiders, and flies too.

Back in the 70s, Dad bought those dangling fly traps. In the mornings, we’d help him open the little cardboard cylinders and pull out the twirling sticky flypaper so he could hang them in the kitchen like decorations. By the evening, they’d be packed full of buzzing and wiggling flies trying to break free of the molasses-like attractant. None of those things bothered me, though, not even the flypaper dangling from our kitchen ceilings or the mice that Dad found each day stuck head-first in snap traps. It was the cockroaches that haunted me.

Our teeth tell stories about us, about the way that we have lived, about where we come from, about our habits, our health, and status.

You always knew that even if you didn’t see them, the roaches were there, hidden within the walls, skittering in the darkness waiting for the light to go down, feeding on the scraps, reminding you of where you came from. They weren’t seasonal like flies, and they did not live in corners, like spiders, making beautiful webs. They could never be the heroine in a favorite children’s book.

They weren’t like the southern roaches either, those slower, bigger, heat-loving cousins called palmettos. No, the German cockroach in New York had a narrative unlike any other. That little six-legged insect that shuns the light with its two thread-like antennae and those hairy legs told a story of filth, of disgust, of poverty and shame. Unlike the southern roaches, they only lived in certain households and, in my child’s mind, they brought with them a label that stitched itself onto every fiber of my being.

*

After I pulled out of the dentist’s parking lot, the blue folder of shame detailing my work plan and pricing scheme on the passenger seat next to me, I drove first to the liquor store then the grocery store. I had called in sick that day. When the Novocain wore off, I was going to drown my sorrows in comfort food and whiskey. Before my appointment I told a friend about my cavities. She said, “I get mine cleaned every six months, and I’ve never had a cavity.” In the car, I wanted to punch her too. I wanted to punch anyone who has ever believed that cavities were a sign of dirtiness, of choice rather than of inequities within our healthcare system. Nobody chooses to have cavities.

As I walked into the store with my swollen face, I was reminded of another cavity I had suffered just before I turned thirty. That cavity took up space on my right incisor very close to the gum. Though it was small enough that I could show some teeth when I smiled, it was still big enough to tear away at my self-confidence. I had been living in a roach-infested two-room studio, working two to three part-time jobs, and paying for community college.

In my first few semesters, I couldn’t afford to buy my books, so I stood in the bookstore aisles at night to read my homework. Other times when I couldn’t get the readings online, I borrowed other students’ books and made copies on the faculty copier. When the manager in my low-rent apartment building moved out, I offered to oversee the building temporarily if the owner would let me live there rent-free. Even with the other part-time jobs and the extra money and free rent, I still had no health or dental insurance.

In my last semester at the community college, I was awarded a full scholarship from the Gates Foundation to transfer to any school of my choice. I picked a program in Costa Rica that was embedded in ideals of experiential learning and human rights. But like many universities, this one didn’t disperse scholarship money until six weeks into the semester, after the school’s census data proved that students had indeed attended. This meant I had to pay out of pocket for upfront costs like travel, books, a laptop, and the first two months of meals.

I could barely afford to eat back then. What was the use in getting a full scholarship to college, when the money wouldn’t even become available until two months into the first semester? I wrote frustrated letter after letter, trying to explain to officials in financial aid that their system was flawed, but there was no give. (Years later I learned that the school fixed this inequity in their financial aid process.)

But while I was still a student at that college, there was no way I could even consider getting my cavity fixed, forget about buying a laptop. It was all I could do to earn and save up the cash for the flight, all the shots and meds needed for international travel, the books and supplies, and then the first two months of lunches and dinners. All of that added up. But I was so desperate to get out, to experience something new, that when renters in my building moved out, I painted, cleaned, and fumigated the roaches on my own for extra money under the table. I offered to clean houses for my friends and professors. By the time August rolled around, I had no choice but to board the plane, broke, with that ever-growing cavity.

I hoped that I could hide that blackening incisor until the next year when I could use the leftover scholarship money to fix it. But I stood out in too many other ways for people not to notice. Most of the students were white and rich and very young. I was a brown woman, and by the time my plane touched ground in Costa Rica, I was thirty years old. Other students had brought spending money with them to take salsa lessons or photography courses or to taxi to San Jose for nice dinners. They all had their own laptops and cameras and hiking gear. They went away to the coast on weekends and they had parents who sent them money when they ran out.

I had less than a hundred dollars to last me the next two months. I ate the breakfast and dinner allowed by my homestay, and a few days a week I bought a bottle of Cherry Coke and thirty-cent tacos from the taqueria near the school. Every time someone pulled out a camera there was another person asking me to smile, someone else saying you’re so beautiful. Someone else watching from the side, waiting to get a glimpse of my rotten tooth. I knew they saw it—that growing black hole defining the essence of my humanity.

*

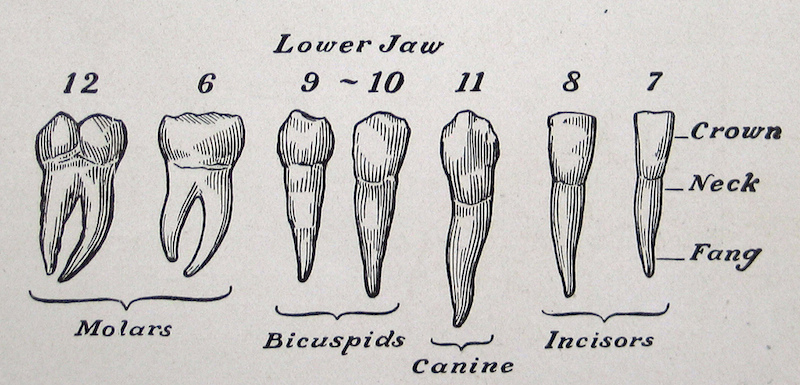

Humans have four kinds of teeth: incisors, canines, premolars, molars. Each tooth has a specific job to do and each one can tell a different part of the story about the way a person has lived. While most of our molars are formed when we are babies, the third molars—otherwise known as wisdom teeth—are the last ones to appear and don’t often erupt until our late teens to early twenties. Consequently, researchers can tell where a human was during each of these formations and eruptions. The minerals from the geographic area are literally cemented into the layers of the burgeoning enamel. Based on how long it takes for all of our permanent teeth to erupt, researchers have also learned that humans take longer to grow up than any other primates.

I wanted to punch anyone who has ever believed that cavities were a sign of dirtiness, of choice rather than of inequities within our healthcare system.

So much of our evolutionary history was spent eating hard foods harvested by hunting and gathering. Our teeth weren’t adapted to a soft and sugary diet. It wasn’t until the industrial revolution that molar impaction and tooth misalignment became ten times more common than it ever was before. Plaque buildup and cavities are a product of a more contemporary diet crammed with refined carbs and an overabundance of sugar. Food habits mark our smiles in such deep and enduring ways that anthropologists have begun to see our teeth as landscapes of histories.

I wonder what my record would say a thousand years from now, after that blue folder disintegrates, after the skin and hair goes back to earth. Would it reveal that I never had roots in any one place, that I left my foster home before I graduated high school, moved in with my boyfriend at seventeen, that I got up every morning of my life and drank coffee with powdered cream and extra sugar before work, that I got by on freezer food and pasta? Where in the layers of my enamel is the evidence that I lived in Costa Rica and traveled throughout Central American countries for over a year? I wonder how that evidence would conflict with the evidence of poverty plaguing my mouth in the form of missing teeth and cavities.

*

After a few months on Berlin Street, Gina and I began scheming ways to stay out later on extermination days. Before we left for school, we’d steal all the change on Mom and Dad’s dresser, tell them we were going to a friend’s house after school. When the bell rang at the end of the day, Gina and I met at the front door and walked through the neighborhood to the bodega on the corner. We’d spend every cent on penny candy. Each of us selecting Fireballs, Gobstoppers, Double Bubble, Banana Laffy Taffy, Smarties Lollipops. Sometimes we splurged on Red Wax Lips, Now n’ Laters, Pixy Stix, Ring Pops, and Pop Rocks.

When we had extra money, we’d each buy a pack of the bubblegum cigarettes—smack them upside down on our palms like Dad did. My favorite was Astro Pops, those cylindrical shaped syrupy suckers in three flavors. Nothing made me feel more like an adult than walking into that bodega, choosing my candy, paying for it, and waltzing out with that little paper bag in my hands. Sometimes we’d walk the streets with candy cigarettes between our fingers, blowing out the powdered sugar and pretending we were smoking.

One day, Gina came home with her friend Latisha. The three of us hung out in our bedroom—candy wrappers everywhere, the Go Go’s on LP—smoking our pretend cigarettes and sucking on our Ring Lollipops when a string of roaches skittered across the back wall behind our bunkbeds. Latisha didn’t see them, but Gina and I were mortified. Gina immediately moved so that Latisha’s back was against the wall.

In school, nobody ever talked about their own infestations; instead, the existence of cockroaches in our classrooms were used as bully’s tools. Whenever one of us spied a roach, some bully would find an especially vulnerable kid to blame it on. Though so many of us lived on welfare in the same kind of detestable conditions, no one was willing to admit it.

*

In the grocery store, I picked up some pasta, sauce, garlic bread, and a Sara Lee Cake. Then in the soda aisle, I grabbed a two-liter of Cherry Coke to mix with my whiskey. I didn’t know if I was going to be able to eat dinner that night, but I was sure going to try. And if I couldn’t chew, then I was going to drink my sorrows away.

Mom had taught us how to make her coffee; “scalding hot with powdered cream and three tablespoons of sugar,” she’d say, “and don’t spill it.” She’d be on the couch, legs up, watching the morning news. We were nine years old when she finally let us pour our own cups. We’d sit on the cushions and curl our legs just like her, blow the heat from the mug, and dip our buttered toast into the sweet creamy mixture.

On Fridays, when there was money, Mom and Dad went shopping. They replenished our pantries with Dino Pebbles and Cocoa Puffs, our refrigerator with two liters of generic cola, black cherry for me, root beer for Gina. When there was no money for soda, we bought eight packets of Kool Aid for a dollar. Lime Aid was my favorite. Once Dad came home with two cases of Ragu sauce. One of his friends at AA came upon a whole truck load of the stuff. When Gina and I arrived home from school, we’d put the sauce on Ritz crackers, slice some government cheese over it, and bake it in the oven like mini pizzas.

When there was money, Dad picked up a dozen doughnuts with the Sunday paper. The four of us would each pick three and take a newspaper section, the comics for me and Gina, the news for Mom and Dad. Junk food was our life, the remnants of which spilled over into my twenties and thirties when I still chose soda over water and doughnuts over salad.

Like so many children in the United States, Gina and I were practically weaned on sugar. But what put us into a different category is that we never went to the dentist, not for regular cleanings, not for x-rays, not for any reason. The cost was too much. And to make matters worse, our parents rarely enforced teeth brushing and flossing. Mom was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in eighth grade and spent the next twelve years in the psych ward. She had lost so many teeth that it was hard for her to chew her food without moving it awkwardly around in her mouth. Gina had chipped a tooth at eleven, falling face first roller-skating down a hill. She never got that chip fixed and the one next to it had a brown cavity for years.

Dad had already lost all of his teeth. When I was very young, he wore dentures. He’d take them out and put them on his bed stand at night. But he lost those too in one of our many moves. I don’t remember Dad with teeth. I mean, I don’t remember what his face looked like with a pearly smile. I only remember those dentures outside of his mouth—sitting on the table or the bathroom sink.

I remember the way he gummed his food, the way his lips were sunk in, the way he turned down the nuts because he couldn’t chew them. He never got another set. Maybe he couldn’t afford it, or maybe he just grew comfortable gumming his food. That’s the thing about humans, we can get used to almost anything, even a cavity eating away at a tooth until severe pain forces a trip to Emergency.

*

When I finally got back to the States from Costa Rica to fix my incisor, the dentist told me that both my front teeth needed crowns and that the bill would be well over a thousand dollars. Because I had prepaid for so many of my college costs, I had enough leftover scholarship money to pay for it. By then I had already lost two other teeth: my second pre-molar on the upper right and the third pre-molar on the bottom right. Neither hurt my smile, neither made it hard for me to chew. I could go through life without those two molars and no one would ever know. It was the front teeth that bothered me. It was those front teeth that would form every perception of me in the future.

Food habits mark our smiles in such deep and enduring ways that anthropologists have begun to see our teeth as landscapes of histories.

After the drilling, when the dentist got up to leave the room and I’d rinsed the blood and ground bone from my mouth, I tongued the empty space around my incisors. Two points poked out of my gums like fangs. I wondered what would happen if he never came back, if some disaster forced us to stop right then. What would the students back in Costa Rica say if they saw me and those two nubbins hanging down from my gums? What would my face look like without those two front teeth? Would my mouth sink in like Dad’s? Would I start chewing like Mom? I was thirty years old and still had three more semesters of college. Could I even get a job looking like that? I told myself that if I were to walk out of the dentist office with those half teeth, then it would be my punishment for all the years of neglect.

*

On Berlin Street, we had so many cockroaches, they came out during the day, especially after Mom cooked a greasy meal. By the dozens they would blacken the sides of the stove and kitchen floor where hamburger or bacon grease spattered. The sight of them moving unnaturally tortoise-like and feeding horrified me. I’d scream for my dad to pick me up and carry me out of the kitchen, make him kill every one of the roaches before I’d walk back in there. At night, if I had to go to the bathroom, I’d scream for Mom to turn all the lights on between my room and the toilet so I wouldn’t accidentally step on any.

When we finally moved out of that place, Mom and Dad had both been working long enough to save up for a security deposit and first month’s rent for a place just outside of the city in Gates. Dad had a knack for finding nice apartments in our budget range. This was a full house in a commercial section on the corner of a busy road. We didn’t care, we were just glad to be out of Berlin Street. Our new house was the last residence in a row of three directly across from the highway’s exit ramp.

In fact, all the houses were so perfectly aligned with the ramp that our neighbors’ front door had been smashed in by a car going too fast off the highway. To the right of our rental was a bakery and large parking lot. Gina and I each had our own rooms and there was even a little yard. And, because we were outside the city boundary, we could go to the suburban school.

By then we had already moved so often that we had rarely spent a full year in the same district. It didn’t change the way we felt about our new home. Every time we progressed to a nicer apartment, it felt like a fresh start. This kitchen had two ovens right on top of each other and an island countertop. The 70s architecture reminded me of the Brady Bunch house, which made it seem even more dreamlike. The living room, with a fireplace at one end, was so big that our little furniture suite from Berlin Street seemed to be swallowed up by the room. The most important thing about this house was that it had no roaches.

he bakery next to us made doughnuts in the mornings and stromboli in the afternoons. I had never had a stromboli, but after that first bite, it became a weekly event. We’d sit around our little kitchen table like a normal family and eat those freshly baked ricotta pepperoni pizza pockets, which were worlds above our slapped together Ragu-slathered Ritz and lime Kool Aid.

It wasn’t long, however, until the first roach appeared in our kitchen. It was just after dinner. Mom was cleaning when she yelled at the “little mother fucker” on the counter. “Goddamned roaches followed us here,” she said, as she slammed her fist down on its hard shell. I was disgusted. How could we have gone so far and still have them? Dad said we probably brought them in our furniture and belongings. I begged them to bomb the house immediately. I never wanted to see another roach again. We were going to a different school with new kids from normal families. Now we couldn’t invite any of them over. If they knew we had roaches, they would know what kind of people we were.

Cockroaches have been around for over three hundred million years. They are a vector of human disease because they feed on waste. They can track bacteria all over a house and multiply at dizzying rates. The German cockroaches, the ones most prevalent in homes all over the world are most often equated to low-income urban housing, they have also been blamed for allergies and asthma in urban children. In the 1970s and 80s, before Combat came along, it was almost impossible to get rid of a cockroach infestation, even with regular fumigation.

Bad teeth aren’t the kind of thing one can leave behind.

I don’t know what made me think that just moving from one place to the next would alter our situation, but that was my first lesson on the nature of change. In my child’s way, I learned that evolution is layered and multifaceted and takes years to actualize. Life doesn’t just flip like a quarter when the situation improves. It’s more like a process of reconstruction, in which only after decades of layering one small change over the last does a new veneer emerge.

By the time we moved out of Gates, I had learned to look for signs of cockroaches in every new apartment we moved into. Even when I moved out on my own years later, in every new apartment I’d pull out the refrigerator and stove to search for forgotten carcasses, scour the cupboards beneath the sinks for the little pepper-sized droppings, comb through the bathroom for the babies with their spotted shells and oblong bodies. I learned how to shake out my clothes before packing in boxes, to inspect the furniture before putting it into the truck.

Years later, when I moved out of my two-room studio to go to Costa Rica, I put everything I owned on the curb, except for some boxes of mementos that I painstakingly took outside one by one to seal into plastic containers. I shook every notebook, every letter, every page of every novel before placing it neatly into a plastic bin. Then I let them sit outside for a few weeks before packing them away into a friend’s attic. I wanted desperately to leave the roaches behind, the last vestiges of my old identity.

*

I was forty years old when I walked down the aisles of that grocery store with a Sara Lee cake in my basket, the blue folder on my front seat—exactly ten years after moving to Costa Rica with a rotten incisor. In the past decade I had gotten a master’s degree, landed an adjunct teaching gig, then a full-time tenure-track position at the same community college I attended. I had become a career woman with healthcare and a retirement plan, but even at forty it wasn’t enough. Our dental plan, like so many others, barely covers serious periodontal issues. Contrary to popular belief, being a professor, especially at the lower levels and especially at a community college, isn’t a high-paying job. I made less money than most of my friends who didn’t work in academia.

It’s no surprise that black and brown children and those who grew up poor feel the inequities of healthcare in deeper ways than children from higher-income families; but what’s not so obvious is what happens to those children when they grow up. They often repeat the patterns again and again. Though I had shed one of the markers of poverty in my life, I had amassed debt from graduate school, from all those years in my twenties and thirties when I had to pay for dental bills out of pocket, or when I had to pay cash for bad brakes on my twelve-year-old car, or when I accumulated dozens of parking tickets for alternate-side parking—sometimes by only eight minutes.

Every time one of those extraneous bills popped up, something else had to give: a late payment on the gas and electric, a missed grace period on the rent, a bounced check to the phone company, a year of smiling for photographs with a blackened tooth. And each one of those tiny acts affected another and another until all of the pins of economy, of status, of credit and career fell into a vicious cycle of struggle. I didn’t even get my first credit card until I walked into that dentist office at forty years old.

That twenty-five-thousand-dollar dental bill was devastating, not just because it was a lot of money, but because I had falsely believed my past was behind me. It was the kind of news I’d learned to fold up again and again, to make so tiny that I’d forget it ever existed. But bad teeth aren’t the kind of thing one can leave behind.

*

I bought my first house a few years ago. But before I put my offer in, I inspected the cupboard beneath the sink, searched the floor behind the refrigerator and stove. Flashlight in hand, got on my hands and knees and inspected every baseboard in the kitchen and bathroom, all despite the fact that I hadn’t seen a roach in over fifteen years. After I moved into this house, with its little backyard, I dug a five by seven plot, which grows a little bigger each year. Last fall I harvested enough tomatoes to make eight quarts of sauce; and between the pepper, eggplant, zucchini, cucumbers, and herbs, I have enough vegetables to eat whole, organic, and healthy for most of the summer.

I still have missing teeth and can only chew hard foods on the left side. But those last two empty spaces on the right are currently fitted with metal posts, one purple and one blue drilled earlier in the year. The dentist says that I have to wait some months for them to heal before permanent crowns can be formed over them.