An upcoming film starring R Madhavan and Akshay Kumar is based on the life of C Sankaran Nair, the lone Indian on the Viceroy’s council whose decision to resign after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre marked a new chapter in India’s freedom struggle.

Today historians regard the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 as a “decisive step” towards the end of British rule in India, turning moderate Indians against colonial forces and even pushing Rabindranath Tagore to renounce his knighthood. It’s an event that resonates with those of us born even generations later, its harrowing details vividly recalled through history in texts, media, photographs, and a survivor’s bone-chilling account.

But in the immediate aftermath of the massacre, things were not so.

The British had several ways to curtail press freedom in India and, in turn, curb the unending wave of anti-government sentiment and vernacular reportage. In an appalling example of just how, British journalist B G Horniman, a staunch supporter of India’s independence movement, was imprisoned and later deported for reporting the massacre and other atrocities taking place in Punjab at the time.

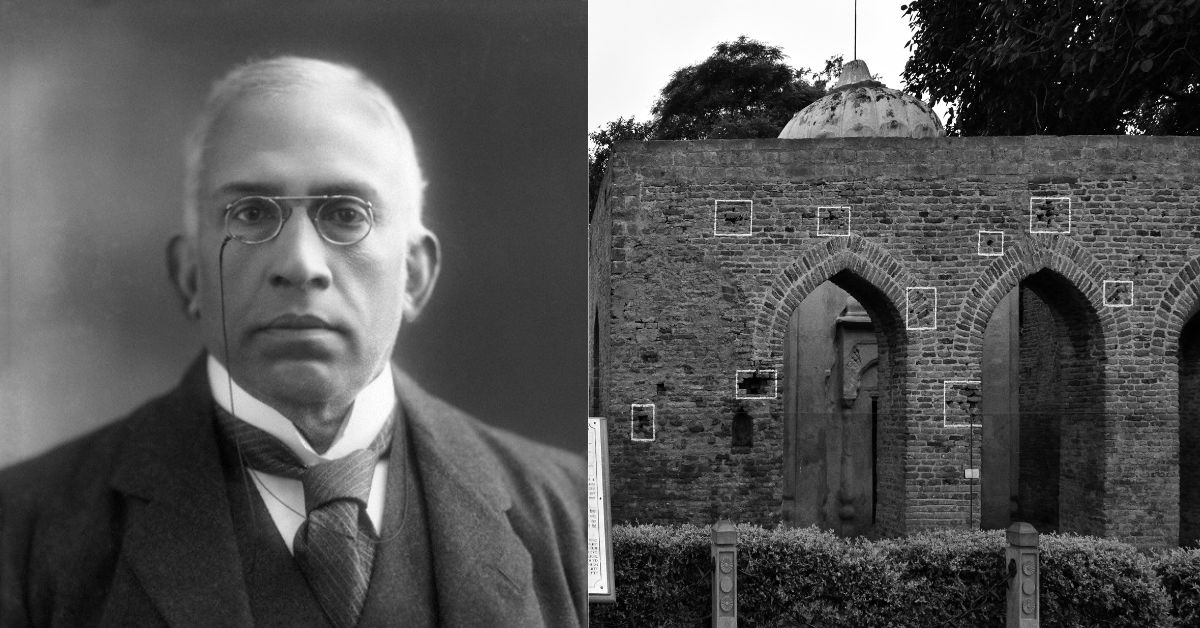

However, further swept under the rug is the story of a lawyer who helped bring the devastating massacre to light — Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair. At the time, Nair was a well-known public figure serving as the only Indian member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, the highest governing body in British India.

When Nair heard of the massacre, he was so horrified that he resigned from his post in protest. His resignation would lead to several immediate reforms, and today, in the circles where his illustrious life and career are known, he is regarded as one “who placed India firmly on the road to constitutional freedom”.

In 2021, filmmaker Karan Johar announced that he would be producing a movie inspired by Nair’s life and the infamous court case he fought against Michael Francis O’Dwyer, then Lt governor of Punjab and considered among the key planners of the attack.

The movie is said to be based on the book The Case That Shook The Empire, written by Raghu Palat, Nair’s great-grandson, and his wife Pushpa Palat. Reports say the film will star R Madhavan and Akshay Kumar in key roles.

But beyond the confines of the historic courtroom drama, Nair’s life was punctuated by several revolutionary transformations in the years that India struggled for her freedom.

A reformist by heart

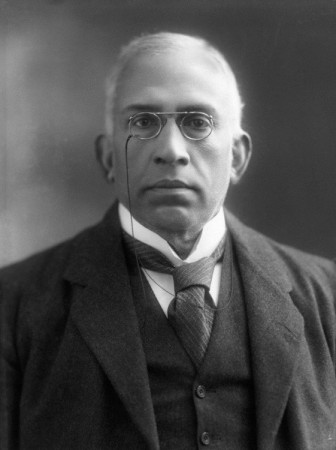

Nair was born in 1857 in the village of Mankara in the erstwhile Malabar region in an aristocratic family. His schooling began first at home, and eventually, in an English-medium school in his hometown, where he recalled performing well, despite his early learning years being centred mostly around Sanskrit.

Of his time in college at Presidency College, Madras, he reminisced, “All our professors in those days were Englishmen. [They] allowed us full freedom of speech…On one occasion, we had to write an essay on the declaration of independence by America…There were some of us who wrote that England must behave better in India, otherwise Bombay would be another Boston Harbour. Our principal took it in good part. In these days, it would have been a matter probably for the C.I.D.”

Towards the end of the 1870s, Nair pursued his law degree from Madras Law College and began his career in the Madras High Court, soon becoming a member of the Madras Bar.

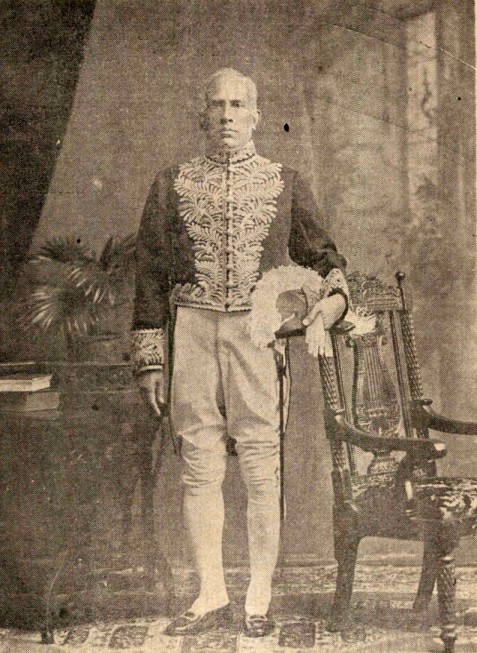

Over the next decade or so, his career would grow from strength to strength — in 1890, he was appointed to the Madras Legislative Council and would become deeply involved with the Indian nationalist movement. In 1897, he was elected president of the Indian National Congress, and in 1907, became the first Indian to be appointed advocate general of the Madras government. Later the same year, he became a judge at the Madras High Court.

In their profile of Nair, the INC wrote that though a reformist by heart, his official work interrupted much of his life as a free political thinker. Meanwhile, Open Magazine editor Nandini Nair opined that “In the pantheon of freedom fighters, Sankaran Nair is often overlooked because as a constitutionalist he opposed Mahatma Gandhi’s methods.”

Regardless, in his time, Nair used his political standing to oppose “extremism in words and deeds”, the mixing of religion and politics, and “exaggerated nationalism”. He was a proponent for the abolition of infant marriage and caste, and the introduction of primary education for low-income groups. Nair, perhaps inspired by the family that he had grown up in, where inheritance was a female right as opposed to an advantage often exploited by men, was also a fierce supporter of women’s equality.

At a time when he held a position that was coveted — and deemed unattainable — by Indians, he also played an integral role in the Reforms Act of 1919, which “expanded the participation of Indians by introducing diarchy in the provinces, under which elected ministers were responsible for subjects such as education, health and local self-government,” wrote Nandini Nair.

‘The most glorious and golden hour’

Meanwhile, the same year, Punjab — and the rest of India — was reeling under the aftermath of Jallianwala Bagh. Years later, KPS Menon, Nair’s biographer and son-in-law, would call the senior leader’s subsequent resignation from the Executive Council “the most glorious and golden hour of Sankaran Nair’s life. His star was never brighter.”

Such was the curtailing of freedom of the press in Punjab that at first, Nair, even at that height of political power, did not hear about the events in Amritsar. From the reporting of the events to the number of casualties, many facts and figures were distorted by the British so as to not let the severity of the act leak to the public at large.

But when the news did trickle down to the public and reached Nair’s corridors, he was outraged. Of his decision to resign, he wrote, “Almost every day, I was receiving complaints personally and by letters, of the most harrowing description of the massacre…and the martial law administration.”

“If to govern a country, it is necessary that innocent persons should be slaughtered…and that any civilian officer may, at any time, call in the military and the two together may butcher the people as at Jallianwala Bagh, the country is not worth living in,” he said.

At the same time, he noted, he found that “Lord Chelmsford (then Viceroy of India) approved of what was being done in Punjab”. In The Case that Shook the Empire, the authors recalled that Chelmsford thought Dyer’s treatment of Indians in Punjab to be “very [reasonable] and in no sense [tyrannous]” and that “in these circumstances, an error in judgement, transitory in nature, should not bring down upon [Dyer] a penalty which would be out of proportion to the offence…”

“That, to me, was shocking,” Nair recalled.

At first, Nair delayed his resignation at the behest of Annie Besant, with whom he shared a cordial relationship. Motilal Nehru and Charles Freer Andrews, a priest and friend of Gandhi’s, were among those who requested him to stay, hoping that he would use his position to advance India’s cause. “But things, at last, became intolerable,” he recalled.

Nair officially resigned in July of that year, and when he returned to Madras, he was received with love and adulation, ovations, feasts, and celebratory bursting of crackers.

Owing to the disputed reports of the massacre, the All India Congress Committee demanded an inquiry into the extent of the role of the British and requested Nair to visit London to lobby for an investigation into the matter. Nair wrote, “I was determined that if I could possibly manage it, there would be no Jallianwala Bagh again in India.”

He insisted that the British government condemn Dyer’s actions and heavily criticised Michael O’Dwyer for his role in the massacre in his book Gandhi and Anarchy, while also opposing Gandhi’s views on non-cooperation.

‘The case that shook the empire’

The book would mark the most well-known chapter of Nair’s life. Unwilling and refusing to render an apology to O’Dwyer for highlighting the official’s role in Jallianwala Bagh, Nair was dragged to court after being sued for defamation.

He was tried at the Court of the King’s Bench in London before an English judge and jury, and his case, reported by The Wire, was followed by the entire world, in effect finally bringing to light the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and the atrocities that the British empire had been inflicting on India. The case lasted five weeks, and was, at the time, the longest in the court’s history.

The bias of an all-English panel in court resulted in the results being in favour of O’Dwyer and Dyer, and all jury members but one voted against Nair’s favour. However, on not having a unanimous verdict, the court offered Nair an option for a fresh trial. Nair immediately refused, believing that “twelve different English shopkeepers” would hardly give him a different verdict.

He was then offered two choices — provide an apology or a sum of 7,500 pounds. For Nair, the obvious choice was the latter.

Though the verdict was not in Nair’s favour, the effects of his efforts to bring the tragedy to light saw almost immediate effects. He recalled, “The press censorship was at once abolished. Sir Michael O’Dwyer announced within three or four days of my resignation that the martial law would soon be rid of, and it was actually cancelled within less than 15 days.”

Nair’s resignation also resulted in the constitution of the Hunter Commission investigating the events at Jallianwala Bagh. It had both Indians as well as the English look into the matter.

Then secretary of state for India, Edwin Montagu, once thought of Nair as “that impossible man”, but his integrity would eventually help the Englishman realise that the lawyer “wielded more influence than any other Indian”.

Perhaps this is why, even as Nair eventually fell out with the Congress owing to his views on Gandhi — an event widely regarded as the reason why his contributions faded somewhere so far into the background — his cause strengthened the nationalist movement and marked the beginning of the end of the British empire in India.